362.

That’s how many players there are on 2019-2020 NHL rosters who are alumni of the Canadian Hockey League. Specifically, the Western Hockey League, Ontario Hockey League, and the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League.

To put that number in perspective, there are currently 692 active players in the NHL. 52 percent of them came through one of those three amateur, or major junior, leagues. It goes without saying that this pipeline has been an incredibly abundant talent source for NHL teams.

Since the OHL’s official inception in 1980, it has been responsible for a number of Hall-of-Famers’ formative hockey years. The likes of Wayne Gretzky, Ron Francis, Eric Lindros, Steve Yzerman, and plenty more have passed through the 20 OHL teams on their way to storied NHL careers. As for players on current NHL rosters, the OHL lays claim to the amateur years of Sidney Crosby, Connor McDavid, Patrick Kane, Gabriel Landeskog, Matt Duchene, P.K. Subban, and many others.

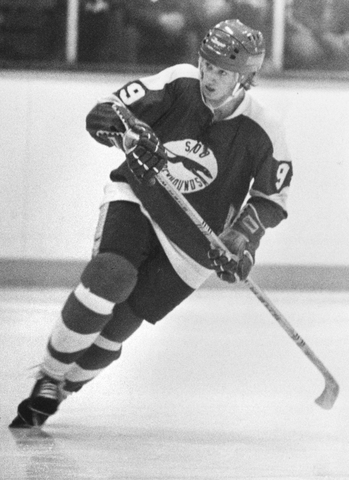

Credit: Kelowna Rockets

The WHL’s 22 teams, though not quite as prolific as the OHL, helped rear Hall-of-Famers like Joe Sakic and Jarome Iginla, while also claiming current players like Shea Weber, Jamie Benn, Ryan Getzlaf, Jordan Eberle, Patrick Marleau, and Duncan Keith.

The QMJHL is not as talent-conglomerating as its other CHL counterparts, as it has resulted in the careers of Mario Lemieux and Martin Brodeur, among other native Quebecois players.

This massive network of some of the most noteworthy past and present NHLers can be attributed to a few key factors.

First, the CHL pays its players. A large portion of the umbrella organization’s income comes from basic revenue generation on game days. A smaller, but significant portion is funded by former CHL players who were drafted into the NHL and have since turned pro. The CHL calls it a “development fee” and justifies the charge because the league has essentially become what Triple-A baseball is for Major League Baseball- a farm league.

It should be noted that while CHL players are paid, it is mostly via stipends that barely equate to minimum wage. See the press release for the class action lawsuit filed in January 2018 here.

Credit: CHL

Second, highly scouted teenagers can be drafted and sign CHL contracts at 15 in the WHL and 16 in the OHL. This ensures that such players’ formative years will be entirely spent in NHL focus- an obviously appealing upside for young hockey players.

While paying its players, the CHL also allows for them to sign their own endorsement deals and receive funding for outside education opportunities. CHL players do not have to pay out of pocket for any equipment, travel, or medical expenses as the league covers them for such things.

Probably the most key reason for the CHL-NHL pipeline however, is that most hockey players are of Canadian nationality. No surprise there, but being Canadian is far more advantageous if you’re wanting to play in the CHL. Canadian players can be drafted into virtually any team in the WHL or OHL (with the exception of Quebecois players, who have to be drafted into the QMJHL), no matter which province they originate from.

American-born players in certain regions must exclusively play in one league or the other due to league “ownership” of their specific region. It’s not a huge disadvantage- both leagues are highly talent-laden. But it does limit the number of premier development teams American kids can play for. The OHL commandeers a United States zone that effectively spans every state from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean, which leaves ownership of the western U.S. to the WHL.

This season, 2019-2020, boasts 182 American-born players on NHL rosters. 120 of them would be OHL-eligible, while just 62 of them would be WHL-eligible. States on the eastern seaboard have always been the primary nexus of American hockey, so the OHL has priority on two-thirds of American players.

Regardless of whether you play in the OHL or the WHL, chances are if you’re a North American hockey player and have a shot at the pros, you will be funneled through this CHL-NHL pipeline. There are exceptions; this year’s #1 overall NHL draft pick, Jack Hughes, turned pro by way of the U.S. National Team Development Program. As did Seth Jones, Jack Eichel, Dylan Larkin, Phil Kessel, and several other less notable NHLers. Those four aforementioned players are exceptional talents, however. Jones went fourth overall in the 2013 draft, Eichel second overall in 2015, Larkin 15th overall by Detroit, and Kessel fifth overall in 2006.

Both the NDTP and the Hockey Canada Development Program are excellent showcase opportunities for young stars, but they maintain a very select roster with only 22-23 players in each age category and primarily compete on international or collegiate levels. Compared to the CHL, the competition isn’t nearly as steep. After all, once you’re in the NHL you stop competing against other countries and likely start competing against some of your countrymen. The road less traveled isn’t always the best, let alone most feasible career move.

The pipeline has faced a decrease in their NHL Draft showing since 2015, however. The CHL consistently claimed about 50 percent of all drafted players each year before then, but has since dropped to 32.7 percent in the 2019 NHL Draft. This has called into question the success rate of CHL competition and if national development programs are actually gaining ground on a more modern training strategy for young players by competing against older, more experienced USHL and NCAA players.

No matter what, the Canadian Hockey League is going to adapt. The most prosperous path to the NHL 40 years running isn’t going to fade away with the emergence of finer tuned national teams. At least not without a fight.